LIVER FLUKE

LIVER FLUKE & GOATS by Rachel A Jones & Priory Vets, first published in September 2022 'Pygmy Goat Notes'

Summary: Goats are highly susceptible to liver fluke, which can cause liver damage, weight loss and anaemia, and goats don’t seem to develop any immunity. Goats are most at risk if they graze on areas of wet pasture. Unfortunately, there is now evidence in sheep that fluke are developing resistance to the most effective drugs, so it is important not to treat for fluke without being confident that your grazing is infected. Farm vets will be on the alert for signs of fluke because they will probably have been seeing cases in other livestock.

The liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) is able to infect goats, sheep, horses and cattle and the resulting disease is called fascioliasis. Acute fascioliasis results in liver failure and sudden death and is caused when large numbers of the immature form of the fluke are ingested over a short period of time. This is generally unusual in goats, which tend to browse rather than just eating grass; however, it may happen if your goats are confined to a small area with only grass to eat, if that grass is infected. In goats, it is more common to see the chronic form of fascioliasis. This is which is when the fluke is present in lower numbers, but is increasing and living out its life cycle in the goat’s body, damaging the liver and feeding on blood; causing anaemia and weight loss. Faecal egg counts can usually detect this stage, because the mature fluke produces eggs, which are passed out in poo.

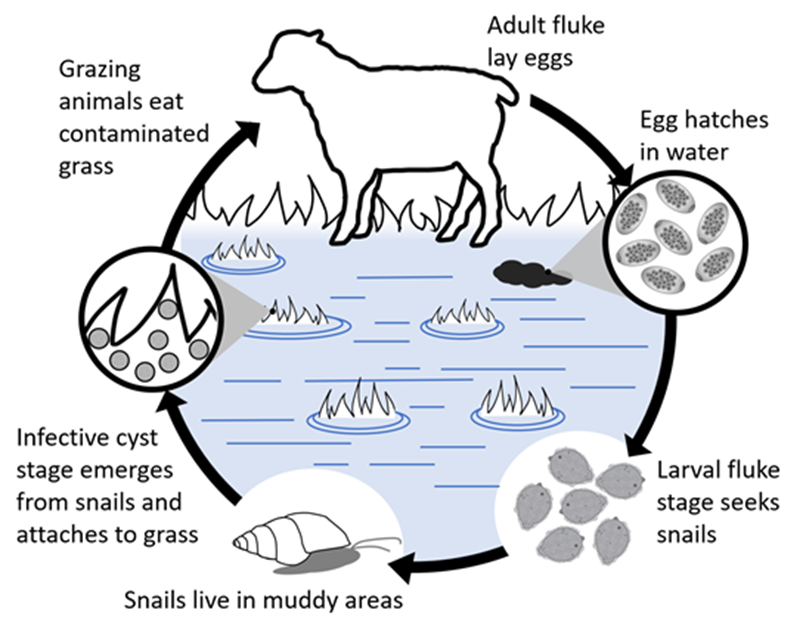

Fluke life cycle. Source: NADIS.org.uk

The life cycle of the liver fluke relies on a particular species of mud snail that is found in boggy/marshy areas, often with rushes, and which are usually found near permanent sources of water. Therefore you are mainly at risk if your land is wet and if it has previously been used to graze other livestock, which may have infected the pasture.

The life cycle of the parasite means that there are certain times of the year when snails are more likely to be shedding the immature infective stages of the fluke into pasture. Various organisations produce fluke risk forecasts for different areas, based on temperature and rainfall, which are sent to farm vets. Generally the west of the UK has the greatest issue with fluke.

Having an awareness that your land might be at risk from fluke can be important to bring to the attention of your vet, who can then advise further. If fluke is identified, it is important to develop a plan with your vet to control the issue, and prevent reinfection of your animals. Measures can include treating animals with flukicides that are targeted to the specific life stage of the parasite, draining or fencing off wet areas, or avoiding grazing these areas during at-risk periods.

Not all mud snails are infected with immature fluke, so if you do not currently have an issue with liver fluke on your land, it is important to keep your pasture clean and parasite free. The main source of new infections is infected animals. Therefore, when buying in new goats (or any other livestock), always be aware that they may be infected with parasites which can contaminate your fields and bring illness into your herd. It is advisable to visit the farm or smallholding where the goats were previously kept in person and talk to your vet if you know or suspect that there may have been an issue with fluke. Faecal egg counts for fluke are slightly more complicated than for standard worm eggs, because the parasite only lays eggs at certain stages of its life cycle, but even if a vet cannot do this in-house they will be able to send it to a dedicated lab. Most vets can check for other common parasites such as worms or coccidia in-house, all that is needed is a sample of fresh poo (min 10g). In the meantime keep new goats quarantined and on hardstanding, so that their poo can’t infect your fields.

Source: Diseases of the Goat by John Matthews (4th Edition)